First off, hey, no writer’s strike after all! The agreement isn’t completely finalized yet but that’s just a matter of formalities at this point. For better or worse, the T.V. landscape shall continue as normal.

Anyhow, when you think “art scam”, what comes to mind? Unscrupulous souls passing off the work of old masters as the real deal? While that sort of thing can and does happen to this day, art scams come in far more shapes and sizes than defrauding the wealthy through an auction house. Just today one hit far closer to home in the form of a contact Dawn received through her gallery website:

Greetings!

My name is john glenn from SC. I actually observed my wife has been viewing your website on my laptop and i guess she likes your piece of work, I’m also impressed and amazed to have seen your various works too, : ) You are doing a great job. I would like to receive further information about your piece of work and what inspires you. I am very much interested in the purchase of the piece (in subject field above) to surprise my wife. Kindly confirm the availability for immediate sales.

Thanks and best regards, john.

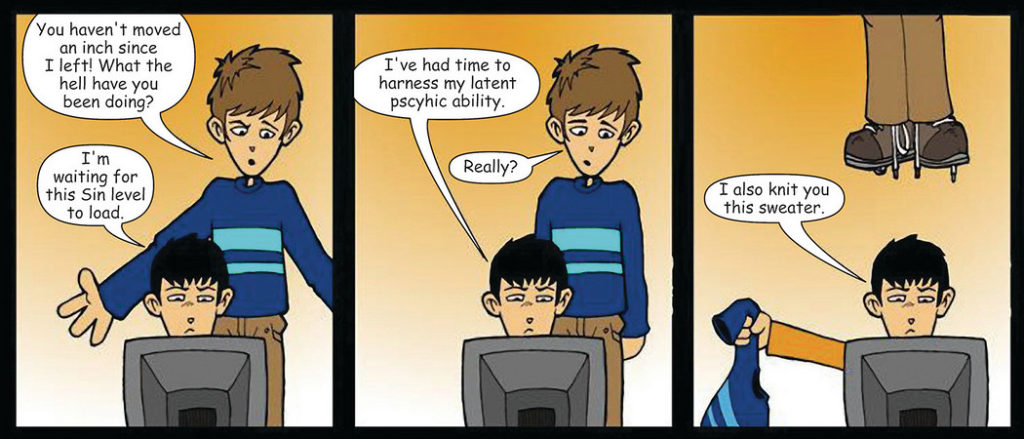

An email like this wouldn’t necessarily raise red flags since we’ve gotten legitimate contacts in the same manner that also offered compliments and sales inquiries, but the immediate suspicion here is how this wording is as flattering as it is vague. If this was an email about the Duckiecorn pins Dawn just listed on Etsy, why wouldn’t it mention that? Oh, apparently the piece in question was in the subject line, so I asked Dawn what the subject line was.

It was simply, “Other.” And no, Dawn has no piece of that name.

Welp, I find when there’s any question of legitimacy, one of the best things to do is just copy a few lines of the email verbatim and paste them into a search engine and see what comes up. See, one thing scammers and spammers have in common is the laziness of whatever program or bot they use, which tends to send the exact same message, poor grammar and all, to hundreds of different recipients, with only the name and email varying. If I found the same message from “john glenn” reported by another artist, or perhaps even more damning, the same message but supposedly sent by “Henry Cameron” instead, then we can safely discard the message as illegitimate. Lo and behold, one of the top hits on the search engine led to this article: How to Recognize an Art Scam.

And the most recent comment at the time, as of yesterday? A report of “My name is Henry Cameron from Ohio. I actually observed my wife has been viewing your website on my laptop and i guess she likes your piece of work, I’m also impressed…”

Scrolling down the comments I saw the pattern repeated several more times as well. It’s all pretty blatant once you know what to look for. Needless to say, “john glenn” is not getting a response.

If you’re an independent artist, it’s important to be able to spot these scams up front, because just like with the classic Nigerian 419, the first mistake is starting a conversation at all. Even if you use a fake email address of your own and intending to troll them back, you’re still wasting time I’d argue is better spent elsewhere. If you don’t use a fake email, or even worse have other contact information in your email, that’s trouble. The original contact will usually be done by a spambot of some sort, but after that you’re going to get the attention of a real live asshole who may never stop bothering you even after you start to smell a rat.

What do they get out of this? Well, this particular version we got didn’t get too cheeky up front, but I have no doubt that they would soon be asking for our detailed contact information so they can “send a check” ASAP. Contact lists are valuable stuff in this day and age and for many independent artists their home and business addresses are one and the same. Now even if you renege on the rest of it, they have something to sell for their trouble.

But that’s not the ultimate goal. The ultimate end is that after they waste your time getting you to send them images of your art (which… weren’t they on your site?), they’ll mail you a cashier’s check (often international but sometimes appearing otherwise) for some amount more than agreed upon, often $1000 extra. If you attempt to cash this it may seem to go through, but here’s the rub: cashier’s checks are something that your bank credits you for on the spot, but it’s a phantom credit. Especially for a check that originated internationally, it can take a few weeks to confirm legitimacy, and if it happens to bounce at the end of that, the bank will just reverse the deposit.

That means you, the depositor, end up on the hook for any of that phantom money. If you spent any of it you may even be in the red now. But again, that’s a few weeks down the road, and those weeks are the magic time for the scammer. Somewhere between then and now, you will be contacted with an apologetic note that the check was accidentally written for a larger amount than intended, and your “buyer” will ask either that you refund the difference to them or forward the difference on to a shipping company the buyer contracted for the shipping and handling fees. The shipping company is, of course, a fake front. Ideally they want you to now do this by wire transfer since those are non-reversible, non-refundable transactions, and by the time your bank lets you know the first check was a fake, your real money is in their hands.

To sum up: You and your “buyer” agree to, say, a price of $1000 for artwork. They send you a cashier’s check for $2000. You inform them (or they inform you) of the mistake, and they say to please return or forward the extra $1000. Then, too late, you find out that $2000 check is worthless, but your $1000 “refund” was all too legitimate. You’re out all that time, that effort, your personal contact information, that money, and possibly even some artwork if you shipped it off. But at that point count yourself lucky if they just disappear, rather than continuing to harrass you or passing your information off to someone else who will. You already proved an easy mark once, right?

And that started just because you responded to what seemed like a very friendly and innocent business opportunity.

This is, of course, all highly illegal, but it’s very rare for law enforcement to be able or willing to do anything other than make sympathetic noises and suggest you be more vigilant in the future.

Well, for most independent artists, that’s not something we can afford. So be vigilant now, because just a few minutes of research can save a lot of heartache in the future.